Wildfires and Mountain Lions

- Nov 19, 2019

- 12 min read

Ecological Inquiry Project:

This assignment required me to carry out an empirical ecological inquiry that addressed a research question focused on measuring biodiversity and current conservation topic. I needed an ecological field sampling with a minimum of six hours of data collection. My topic focused on if there is a difference in plant abundance in burned versus unburned areas.

This was created for my Regional Ecology: Biodiversity of Southern California course in Fall 2019.

Abstract

Mountain lions are the apex predator in the biodiversity hotspot that runs through San Diego, California. Wildfires are also prone in this area. This study took place at four locations in Mission Trails Regional Park, in two burned and two unburned areas. The goal was to determine if there was enough plant abundance in either area to see where deer are more likely to gather for feeding. A one diameter meter circle was used to collect the presence or absence of plants and what type of plants were present. The results showed that new grasses are growing in the burned area and could be better feeding ground for deer due to the plant abundance. More research is needed to know for sure where deer and mountain lions would be found before and after a fire. This paper will focus on if there is a difference in plant abundance in burned versus unburned areas.

Introduction

There are 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world taking up 2.4% of the Earth’s surface (Conservation International, 2019). San Diego, California is a biodiversity hotspot as well as one of five Mediterranean-type ecosystems on the planet (Conservation International, 2019). This type of habitat includes mild climate and drought deciduous shrubland (Conservation International, 2019). Southern California’s biodiversity hotspot supports the greatest number of threatened and endangered species in the United States (Luke, 2004).

Wildfires are a natural occurrence in Southern California and are crucial to the proliferation of certain plant and animal species, however, humans have increased the rate at which fires occur causing significant changes in the environment (Goldman, 2019). Wildfires historically occur every 30 years allowing the native chaparral and other plants time to grow back and have the environment begin again (SDNHM Wildfire, 2019). Chaparral is found throughout Southern California and can be used as fuel during a fire, which can create embers that the wind can carry over 5 miles away and continue spreading the fire (MTRP Fire, 2019). However, climate change is increasing the fuel and temperature allowing fires to occur every 15, 10 or 4 years allowing the invasive plant life to grow and take the place of the native plant species, since the native plants take longer to grow back (SDNHM Wildfire, 2019). Climate change is the biggest driver of wildfires due to increased droughts, fuel build up, earlier spring seasons and higher temperatures (Daley, 2017 ). On average there are 61,375 human caused fires resulting in more than 2.8 million acres to being burned each year here in the United States (NIFC, 2018). Pyrodiversity is a really important event in wildlife habitat, however, today we have more fires that are burning hotter and larger than what the habitat can handle (Goldman, 2019). This is leading to a decline in pyrodiversity (Goldman, 2019). Pyrodiversity is the effect fire creates and promotes on biodiversity in an environment and is abundant in southern California (Kelly & Broton, 2017). These hotter, faster, and rapidly recurring fires have massive implications for the various flora and fauna in California, including the apex predator in the United States, the mountain lion.

The mountain lion (Puma concolor) is the most efficient large predator in the United States (Williams, 2018). Mountain lions are opportunistic stalk and ambush hunters that favor preying on deer (Hansen, 1992). A female mountain lion with cubs will make a kill once a week, while a male will make a kill every couple weeks (Williams, 2018). They can eat up to 20 pounds at one time, and they save the rest for later, visiting the kill over the next few days (Williams, 2018). A female mountain lion needs about 20 to 60 square miles of habitat, while a male needs about 100 square miles of habitat (CDFW, 2019). In some areas where there is little land yet competition for habitat, there can be as many as 10 adult mountain lions in the same 100 square mile habitat (CDFW, 2019). California is 155,959 square miles of land with 46% of the state being suitable habitat for mountain lions (MLF, 2019). It is difficult to pinpoint the mountain lion population in California but it is believed to be around 4,000 to 6,000 (MLF, 2019).

Mission Trails Regional Park is a 7,220 acre natural and developed area in San Diego, California (MTRP Park, 2019). It is one of the largest urban parks in the United States, and has prime mountain lion habitat throughout the park (MTRP Park, 2019). On March 6, 2018 a fire erupted at Mission Trails Regional Park. The fire grew to 1.5 acres in between two bodies of water, the San Diego River and Kumeyaay Lake, in a marshy area (Self, 2018). Although the fire was small, it did affect the wildlife in the area. Mountain lions were likely affected by this fire in terms of their own safety and their ability to hunt for food once the flames were extinguished (National Park, 2019). During a fire wildlife flee the area in search of finding safety, for this particular fire they did not have to flee very far but they still left the area. With no prey present, there is a chance that mountain lions will not be present since they will follow their prey. After the fire is out there is a possibility that most animals will come back. With more rain comes more plants, and with more plants comes more prey which makes it a prime time for mountain lions to hunt deer (SDNHM Chaparral, 2019). Mule deer like to forage on new growth after a fire, which could lead to an increase in mountain lion kills (Goldman, 2019). This paper will discuss the difference in plant abundance in burned and unburned areas.

Methods

The study took place at Mission Trails Regional Park in four locations, two locations were in an unburned or fire-free area and two locations were in a burned area. The plots in the unburned area away from water took place on the Climbers Trail, which happened to be uphill. Climbers Trail is the name of that particular trail. The plots in the unburned area near water took place on the Grinding Rock Trail, which happened to be on flat ground. The burned area away from water was on the Nature Trail and fire road in the Kumeyaay Lake Campground. The burned area near water was on the marsh between the San Diego River and Kumeyaay Lake on the Nature Trial in the Kumeyaay Lake Campground. In the burned area, the study sites near-water and away-from-water were close together because the burned area was not that large or easily accessible. The area was surrounded by native habitat restoration projects and signs asking to stay on designated trails and stay behind fences for everyone's safety. In order to follow the rules of staying on the designated trails at all times altercations had to be made where the one meter in diameter circle was estimated since I could not physically go out to the burned area to collect the data. There is a map of Mission Trails Regional Park in Appendix A and Appendix B is the same map with the study site locations circled in red.

A plot data lifecycle grid was used to collect data. This method was used to see if there was a presence or absence within the circle since the circle would remain the same size throughout the sampling. The grid was a one meter diameter circle that was randomly placed on the ground to see if there was a presence or absence of plants that deer would eat. Random selection of grid placement was chosen to ensure there was no plots being favored or left out on purpose. The circle was made out of rope and randomly placed in different areas within the study sites. It was checked prior to collecting data that the rope did not have any kinks so there was a full one meter diameter of data being collected. There were a total of 20 plots taken, with 10 being taken in the unburned area and 10 being taken in the burned area. Within each area there were 5 plots taken near water and 5 plots taken away from water to see if there was more of a chance that deer would be around. This was done not only to see if there was a difference in a burned and unburned area but also if there was a difference near and away from water.

Results

The data shows that in the unburned area there was an even mixture of plots with plants and plots without plants. In the burned area every plot had new grasses growing in it and new grasses growing all around. Near the burned area there were also deer prints in soft mud which could have happened that morning. The data in the burned area had to be taken at a distance, but the area was covered in new grasses producing new life after the destruction of fire.

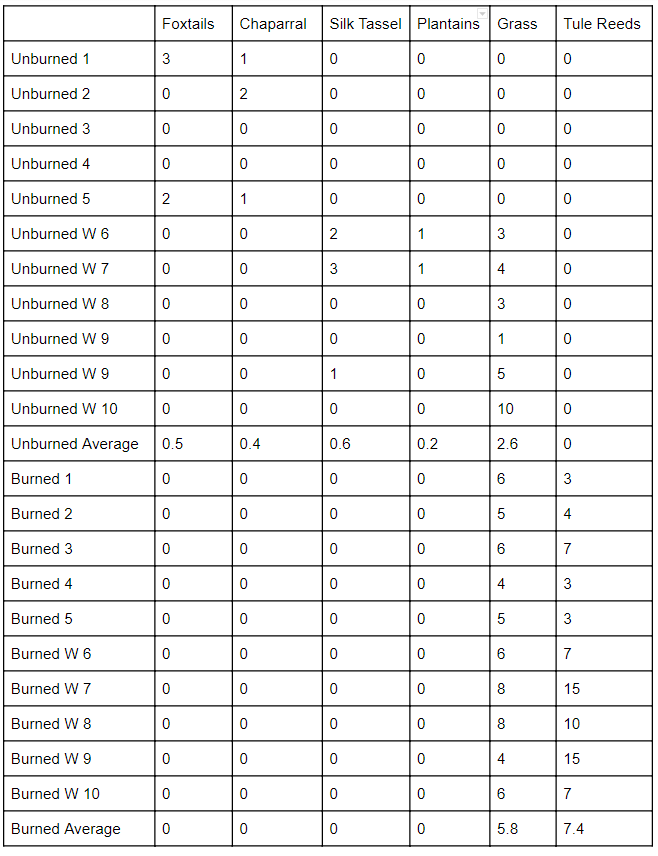

Figure 1: This graph shows the average number of plants and type of plants found within the one meter diameter circle.

Figure 1 displays the average number of each plant found in a 1 meter diameter circle in both burned and unburned areas. Each plant that was seen is included in the graph. All grasses were grouped together in one group termed ‘grass’. There were also tule reeds present which the deer can eat as well. There was more plant abundance found in the burned area but more plant biodiversity found in the unburned area. Figure 1 also shows that the majority of grasses are in the burned area.

Discussion

The majority of plots with plants in the unburned area happened to be near bushes and grass that were bent over. At the time it was assumed it was a spot where an animal would have laid or where an animal could have hidden to hunt or eat their prey. According to one of the signs at the Mission Trails Visitor Center the bent grass was from deer laying down to rest or eat. The results showed that there was more abundance of plants and new grasses were growing in a recently burned area. With the grass growing and the presence of deer tracks it is safe to say that deer are utilizing that area, either by eating the grass, drinking the water, or just by walking through the area. With deer presence in this location it can be assumed that mountain lions may be present in this area while hunting for prey since they follow their prey, and there are plenty of unburned tall grasses and trees in which the mountain lions can hide in. Mountain lions are probably still utilizing the unburned area, but they probably venture near the burned area to hunt for deer. The data may be skewed since accurate plots could not be attained due to the sensitive habitat surrounding the area.

The data was collected both on human-made walking trails and next to the trail where plants are normally found. Data was collected both on and next to the trail so there is a possibility that human presence affected the data. Deers and other animals could have affected the area as well. The study sites near the burned area was on a campground, however there were five total people on those trails including myself. While in the unburned areas the path near the water had a lot more human activity. The Climbers Trail was a steep incline and not recommended for the average hiker, which may explain why there were no people on this trail. Data was collected on Friday morning which could be another reason why the human population was so small during data collection. There were also large rock formations which are perfect for mountain lions to hide in, and near the rocks was a sign explaining if you continue on the path you are entering at your own risk and it is not suggested to continue, which may be another deterrent to people avoiding that path. The path was very uneven and became very narrow. The path could not be seen because of a turn in the trail about 30 yards past the sign.

Originally data was going to be collected in the Santa Monica Mountains. The unburned study site burned down in the Getty fire, which was caused by a tree branch breaking off and hitting nearby power lines (Matthew, 2019). There were several other fires in the Los Angeles area at the same time so it was decided to change the study site to a safer area and an area where I would not get in the way of emergency personal and residents trying to evacuate. Fires are a natural occurrence with which humans need to coexist. We also must understand that wildlife is also affected by the loss of habitat and prey caused by fires.

Due to the plant abundance of grasses in the burned area it is determined that deer would choose that location to feed. Having deer in that area and the tall grasses and trees surrounding it, it could mean that mountain lions follow the deer to the burned area and stalk and ambush the deer as they eat. More data is required and data on the actual burned site is required to know for sure if mountain lions and deer are present in the area. The volunteer and the ranger in the visitor center both said they are unsure how many mountain lions are in the park or if they pass through. They do know that because they have deer, mountain lions are present at times but encounters with humans are very few and far between. Although the fire was one year and eight months ago it looks like the plants are still growing, which could be a sign that the grasses are native rather than invasive. The newer looking plants are much shorter, by a couple feet, than the older looking plants. It looks like deer are frequenting the burned are more than the unburned area, possibly due to the new fresh grasses that are growing. There were no deer tracks seen in the soft dirt of the unburned area, but that does not mean deer are not present in that area. More research and data is needed to come to a fully detailed conclusion.

Fire effects on fauna are still being discovered so there is extremely little knowledge on how wildfires affect mountain lions. Generally predators are most negatively affected by fire and the effects can occur in three levels (Engstrom, 2010). The three levels are first-order (direct), second-order or indirect, and evolutionary effects; all of which correspond to first fire, second fire and third fire (Engstrom, 2010). In first-order the effects last a short period of time, usually days or weeks, and consist of injuries, death, or motivation for the individual to move from or into a burned area (Engstrom, 2010). During this time there are high temperatures, toxic effects of smoke, oxygen depletion which can all cause death or impairment (Engstrom, 2010). During the Mission Trails fire mountain lions and deer could have left the area to avoid these dangers, or they could have both been stuck in the toxic smoke. Second-order occurs as vegetation succession and causes an issue when enough individuals survive the fire and now there are events of starvation, predation or immigration, (Engstrom, 2010). Lastly, evolutionary effects of fire on animals can modify a species over time to create adaptations to fire (Engstrom, 2010). Although there is still much to learn in animal-fire relationships, it is safe to assume that not much is known about how wildfires affect mountain lions and what the lasting effects are. We do know that how the habitat performs under fire depends on the fire frequency in the area, the intensity of the fire, the season, weather conditions, soil moisture, and fuel load (Engstrom, 2010).

Fire changes the vegetation structure and can lead to increased erosion and a depletion of nutrients (Engstrom, 2010). If the fire changed so many crucial elements of the plant life the deer may not have returned to the burned area in Mission Trails. The fire was almost two years ago so native plant life has started to grow back, bringing the deer to it. The deer most likely avoided the area directly after the fire and stayed away until the plants started to grow back. Since there is a chance that deer will be in the burned area, due to the fresh plants that are growing, this also means that there is a chance that mountain lions can be found in the burned area as well.

Conclusion

Mountain lions are the apex predator in the biodiversity hotspot of San Diego, California. That same area is also prone to wildfires, usually they are human-caused wildfires. The study focused on two areas within Mission Trails Regional Park and had a total of four locations to determine which area had more plant abundance. The burned area seemed to have more plant abundance but less plant biodiversity. Mountain lions attempt to leave areas that are on fire but they come back to that area once their prey return. Deer seem to have more food options in the burned area because the grass they eat grow back and become fresh food for them. With deer eating in the burned area it is safe to assume mountain lions will follow and have more of a chance hunting their prey in that burned area. The unburned area had more plant biodiversity while the burned area had more plant abundance. More research is needed to come to a complete conclusion but I believe both mountain lions and deer are more likely to be found in the burned area to eat, at least in Mission Trails Regional Parks.

Literature Cited

California Department of Fish and Wildlife. (2019). Keep me wild: mountain lion.

Conservation International. (2019). Biodiversity hotspots: targeted investments in nature's most

important places. Retrieved from https://www.conservation.org/priorities/biodiversity-hotspots.

Daley, Jason. “Study Shows 84% of Wildfires Caused by Humans.” Smithsonian: Smart

News, Smithsonian Institution, 28 Feb. 2017, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/study-shows-84-wildfires-caused-humans-180962315/.

Engstrom, R. T. (2010). First- order fire effects on animals: Review and recommendations. Fire

Ecology,6(1), 115-130. doi:10.4996/fireecology.0601115

Goldman, J. G. (n.d.). Forest fires are getting too hot-even for fire-adapted animals. National

Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/08 /forest-fires-too-intense-adapted-woodpeckers/#close

Hansen, K. (1992). Cougar the American lion (1st ed.). Flagstaff, AZ: Northland Publishing.

Kelly, L. T., & Brotons, L. (2017). Using fire to promote biodiversity. Science, 355(6331),

1264–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7672

Luke,C., Zedler, P.H., Shapiro, S. (2004). Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference,

284–293. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download? doi=10.1.1.845.2845&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=296

Matthew, Z. (2019, October 29). Dash cam video shows how the Getty fire started. Retrieved

Mission Trails Regional Park. (2019). Fire related news. Retrieved from

Mission Trails Regional Park. (2019). The park. Retrieved from https://mtrp.org/the-park-2/.

Mountain Lion Foundation. (2019). Mountain lions in the state of California. Retrieved from

Self, Z. (2018, March 6). Fire erupts at Mission Trails Park. Retrieved from

The San Diego Natural History Museum. (2019). Chaparral. Retrieved from

The San Diego Natural History Museum. (2019). Wildfire frequency. Retrieved from

file:///C:/Users/reedt/Downloads/ENGLISH_Grade_7_Wildfire.pdf.

Williams, J. (2018). Path of the Puma (1st ed.). Patagonia.

Appendix A

Mission Trails map.

Appendix B

Mission Trails map with study site locations circled in red.

Appendix C

This table shows the raw data collected during the study.

Comments